Table of Contents

The Olympics announced its second-ever esports series last week, which means that in 2023, video games will be part of the world’s most revered sporting event. Players can sign up for qualifying rounds, some of which are already underway. The series will culminate in a live event in Singapore in June, part of the first Olympics esports week, where qualifiers will compete across nine virtual sports.

This should be a huge moment that the gaming and esports worlds would both be celebrating. Instead, esports professionals have been despairing over the games that have been included. Instead of selecting well-established esports titles – the kind played in stadiums and whose top players earn six- or seven-figure prizes – the Olympics esports series has picked ones based, sometimes loosely, on real-world sports. Instead of Dota 2, Counter-Strike, Hearthstone, Valorant or Overwatch, there will be a free-to-play archery game called Tic Tac Bow, Just Dance, the VR motion-tracking game Virtual Taekwondo, and Gran Turismo.

“For the average esports fan, its inclusion in the Olympics should have been a triumphant moment representing a step forward for the community, which has grown from a few hundred gamers in the early 1980s to over half a billion this year,” says Matt Woods of the esports marketing and talent agency AFK. “Unfortunately, last week’s announcement left us feeling disappointed and, honestly, a little embarrassed. Instead of working with existing game publishers or well-established tournaments, it seems that the Olympic committee has instead decided to use this event as a marketing vehicle for brand-new, poorly thought out, unlicensed mobile games.”

I can see where Woods and his esports industry colleagues are coming from. People have been making a living playing games professionally for decades, and especially in the past 10 years, esports have grown enough to support an entire industry of leagues, agencies, broadcasters, commentators and support staff across many different games. If you were trying to bring competitive video games into an established sporting event like the Olympics, why not tap into this existing framework?

I am sceptical of some of the absurd numbers that get thrown around when it comes to esports – competitive gaming is worth somewhere between $1bn and 2bn, with a global audience of between 200 and 600 million, depending on whom you listen to and how wary you are of investor-baiting braggadocio. But there’s no denying that esports are popular and well-established. The International Olympic Committee has shown little understanding of that world.

Some of the games selected are completely unknown. Archery game Tic Tac Bow, as Woods and other critics have pointed out, has a rating of 1.9 stars on Google’s app store. Some of these games are going for realistic representation of the actual sport, such as sailing game Virtual Regatta, whereas others are … well, Just Dance.

I asked the IOC about its approach to esports, and how these games were selected. “The Olympic Games has always offered a diverse programme, including those sports whose competitors do not benefit from the platform of other high-profile competitions,” a spokesperson responded. “In order to build a similarly diverse programme for the Olympic esports series 2023, we have partnered with International Federations, who in turn propose game developer partnerships … It is important to us that the featured games align with the Olympic values. This includes participation inclusivity, such as technical barriers to entry, the gender split of the player base, and avoiding any personal violence, against the backdrop of the IOC’s mission which is to unite the world in peaceful competition.”

One straightforward explanation for the absence of Overwatch (above) or Valorant is that they are simply too violent. Almost every established esports game involves teams shooting at or otherwise attacking each other, a foundational concept of competitive gaming that unfortunately runs entirely contrary to the Olympics’ philosophy. Each of the nine selected games was suggested by the relevant real sport’s federation, which explains the variation in their nature and styles.

This is, it should be said, only the second time there has been a virtual component to the Games, and the IOC has said it expects to add titles to the lineup in coming weeks.

One thing that’s clear is that the Olympics is using the word “esports” in a different way than the video game world would use it. For gamers, esports are elite competitive games that support leagues of pro players and viewerships of millions. What the Olympics has put together is, instead, a collection of virtual sports, sport simulators and sport-themed arcade games. And honestly, those might be more fun to watch for a general viewer than, for example, League of Legends – but it’s understandable that the esports world is peeved.

What to play

Simon Parkin reviewed Birth last week, a creepy conceptual puzzle game that makes me feel equal parts intrigued and repulsed. It’s about Frankensteining together a companion from found organs and bones to soothe your loneliness. “Birth is a game of symbols and sequences, of spotting the odd one out and arranging trivial things to solve profound things,” says Simon. “It’s about the loneliness you can feel when living in a big city, but is also clearly born out of pandemic lockdowns, of the sense of disconnectedness most of us felt, and the strangeness of adjusting to reconnection. It’s a warm, empathic and melancholic quest in which simplicity makes space for meaning.”

Available on: PC/Mac

Approximate playtime: 2-3 hours

What to read

-

Brendan Keogh explains beautifully why institutions and governments should look beyond how much money video games make when considering how to support them as part of the arts. “Game development must be treated as cultural work,” he writes. “This doesn’t mean simply championing games that make money, but also championing all the practice and experimentation that can sometimes lead to new innovations and success stories.”

-

Pokémon Scarlet and Violet players are losing their save files after downloading the games’ latest updates. As the kids say, big yikes. If you have a cherished collection of Shiny Pokémon, or a child who is very invested in their Quaxly, best to be cautious and avoid updating the game until Nintendo has addressed this issue.

-

Rock Paper Shotgun’s long interview with Marc Laidlaw, writer of Half-Life, is well worth a read for disciples of Gordon Freeman.

-

Martin Doherty told the NME that his Scottish indie-electropop band Chvrches would be “there in a second” if Hideo Kojima asked them to contribute music for another of his games. (The band composed the theme for Death Stranding.) Kojima, for his part, is being typically cagey.

-

As Microsoft’s proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard rolls endlessly on, Axios reports that Microsoft commissioned a YouGov survey to reassure UK regulators that the merger would not encourage PlayStation players to jump ship. It found that 3% of total PlayStation players would switch to Xbox if Call of Duty were made Xbox-exclusive. There’s something quite amusing about Microsoft having to spend the past year trying to prove that its proposed acquisition is actually not as good a business move as it looks.

after newsletter promotion

What to click

Stray and God of War Ragnarök lead nominations at Bafta games awards

From Ghostbusters and Aliens to Lego Star Wars: 10 great video games based on movies

Star players: How Kerbal Space Program’s little green aliens are helping the space flight experts of the future

Hot buttons: why fashion houses are getting into video games

Question block

Reader Adam posits this week’s question: “I’ve been playing Tunic for a while, and this led me to thinking about instruction booklets and other non-digital accessories for games. What are your favourite examples of these and how have they enhanced the gaming experience for you?”

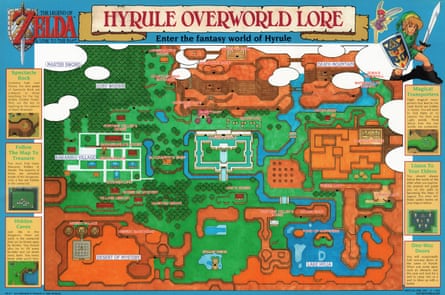

Like all children of the 1990s I have powerful nostalgia for the cardboard boxes that games used to arrive in, crisp corners ready to be scuffed, paper manuals inside with that new-magazine smell. The first game I properly loved, Zelda: A Link to the Past, came with a manual that I read in bed until it fell apart, and a sealed hints booklet that promised the answers to the game’s biggest mysteries. As I peeled back the sticker and took a peek, I felt as if I was about to unearth dangerous, forbidden knowledge. I loved the evocative illustrations in the Zelda games’ manuals: Link facing off against a Deku plant, his sword captured mid-whirl; interesting potion bottles; crafty-looking characters I had yet to meet. In the days before game graphics could look as beautiful as those made with pen on paper, these manuals and guides really fed the imagination. My favourite physical accessory, though, is a game map, the kind that you find in the opening pages of a fantasy novel. Maps mean adventure, to me. I still have a few illustrations of the worlds of my favourite games up on my walls.

If you’ve got a question for Question Block – or anything else to say about the newsletter – hit reply or email us on [email protected].